MOTO STORIES

Working it Out

How working with Nicky Hayden taught the author life lessons about hard work

It was October 23, 2011, still only minutes after Marco Simoncelli’s life had slipped out of him on the asphalt between Sepang International Circuit’s 11th and 12th corners. Pit lane was silent, engineers reverting to numb muscle memory to carry out their duties while riders simply sat and stared, their faces blank with incomprehension. A small group of reporters approached the Ducati Team garage, recorders and notebooks in hand and, catching my eye, apologetically gestured at the young man in the box’s west corner, his red leathers still literally dripping sweat. Understanding their need to file stories on deadline, and my own role as press officer, I reluctantly turned to him: “Nicky, I’m sorry to ask, but do you feel up to giving a comment to the press?”

Without hesitation, he got to his feet, strode across the garage, and spoke at length with the appreciative reporters, his trademark Kentucky drawl only quavering slightly as he paid tribute to a fallen fellow racer. During a horrible, vexing occasion when less-than-admirable behavior would have been understandable, Nicky simply did his job, to the best of his abilities and without protest.

For better or worse, working hard was the only way Nicky ever knew. Earl tells stories of his middle son refusing to come in from training sessions on the Haydens’ Owensboro, Kentucky, backyard track until it was too dark to ride. (That's how it got its Sunset Downs name.) Even when he became a world-famous factory racer, Nicky would invariably turn the most laps of any rider during the unglamorous, monotonous days of testing, not even pausing midday for lunch in the hospitality, but instead wolfing down mouthfuls of pasta from a paper plate while studying timesheets in the garage. (“I don’t get ready,” he liked to joke: “I stay ready.”)

Only once that I’m aware of did Nicky’s single-minded devotion to racing momentarily waver: In 2001, his dirt track teammate, Will Davis, was killed during a Saturday-night Grand National Championship race in Sedalia, Missouri, the same weekend that Nicky had an AMA Superbike round in Colorado. “The next morning was the only time I ever woke up and didn't care about going to the track,” Nicky told me for our 2007 Hayden biography, From OWB to MotoGP. But after a forthright conversation with crew chief Merlyn Plumlee (who himself would pass from cancer in ’07), Nicky won the Pikes Peak national and then commemorated the moment by riding a lap backward and then taking on Davis’s “Chasing a Dream” motto for himself.

I don't think anyone ever loved riding more than Nicky, but as his willingness to be interviewed at Sepang demonstrated, it wasn’t only the relatively enjoyable work of turning laps that he readily assumed. He embraced the entire job of being a professional racer, even the menial promotional duties. Having worked with him as a journalist, author, and fellow team member, I’ve had countless occasions to experience his punctuality and engagement during such tasks, to the point that I’ve been inspired to try elevating my own level of professionalism. When Leukemia unexpectedly took my mother just over a year after Simoncelli’s death, I remembered Nicky’s actions in the Sepang garage and tried my best to perform my duties for him, the team, and my family, even in grief. I like to think his way of repaying those efforts was his staunch availability for the PR favors I regularly asked since then, even after we both left Ducati and went our own ways following the 2013 season.

I’m convinced that Nicky’s 2006 MotoGP World Championship serves as a monument not to exceptional natural ability, but to how far hard work and belief in oneself can take a person. I’m also convinced that, had someone been able to get a 5-year-old Nicky off Sunset Downs long enough to make him an offer--that one day he could be a beloved World Champion with his own statue and a day named after him, but that in return he'd have to work harder than anyone else and then depart this earth at age 36—he’d have readily accepted. It’s fitting, then, that when it came time for Nicky to submit that second remuneration, he was doing his job, devotedly following a training regimen on an Italian road in the midst of a difficult season—still Chasing a Dream.

As it happens, I too was occupied carrying out my obligations the day Nicky died, as I was working a press launch for a Honda side-by-side vehicle at a Texas ranch. Media functions are absurdly busy events for marketing folks, and like every fan of The Kentucky Kid, I was deeply affected by his passing. Still, I again thought back to that 2011 day in Malaysia and gamely shouldered the extra tasks of penning an obituary and press release, and of preparing a tribute video.

The year since then has been marked by occasional moments of profound heartache, along with the colossal workload familiar to anyone who has started a business. Fortunately, I’ve noticed that the latter seems to have helped assuage the former.

Thank you for your example, Champ, and happy Nicky Hayden Day. I hope I’m making you proud.

Return of Llano to Isabella

In a Christmas attempt to recreate a motorcycle trail ride from his youth, the author discovers new friendships

When I was a toddler drooling on the tires of my dad’s Norton P11 as he worked in our garage, the highlight of my year was Llano to Isabella. Technically just a casual trail ride that Dad organized every spring, this event was the equivalent of the Indianapolis 500 in my young eyes—a momentous motorsports occasion that I dreamed of one day participating in myself (beyond merely playing in the dirt at the ride’s various pit stops, that is).

The course ran 200 miles, from our home in Southern California’s Antelope Valley to the Piute Mountains in the southern Sierra Nevada range. Without the benefit of GPS, Dad used to spend evenings plotting each year’s route using a combination of topographic maps and recollections from past District 37 off-road races like the Pasadena Motorcycle Club’s semi-legendary Greenhorn Enduro.

Eventually, I was old enough to experience a couple of sections from the back of Dad’s P11, and when I was given my own XR75 at age 12, he allowed me to join the adults for most of the ride. (I couldn't do the last stretch from Red Rock Canyon State Park to Lake Isabella's Hungry Gulch Campground, for which street legality was required.) Due solely to the fact that I was the trail boss’s son, I was tolerated by the veterans, a colorful lot with names like Uncle Corky, Chucko, Spats, Neil, Wimpress, and the Eaton brothers. When my aunt married, Uncle George was introduced to dirt bikes via Llano to Isabella, his infallibly good nature more than enough to overcome the ribbing he took for riding a two-stroke.

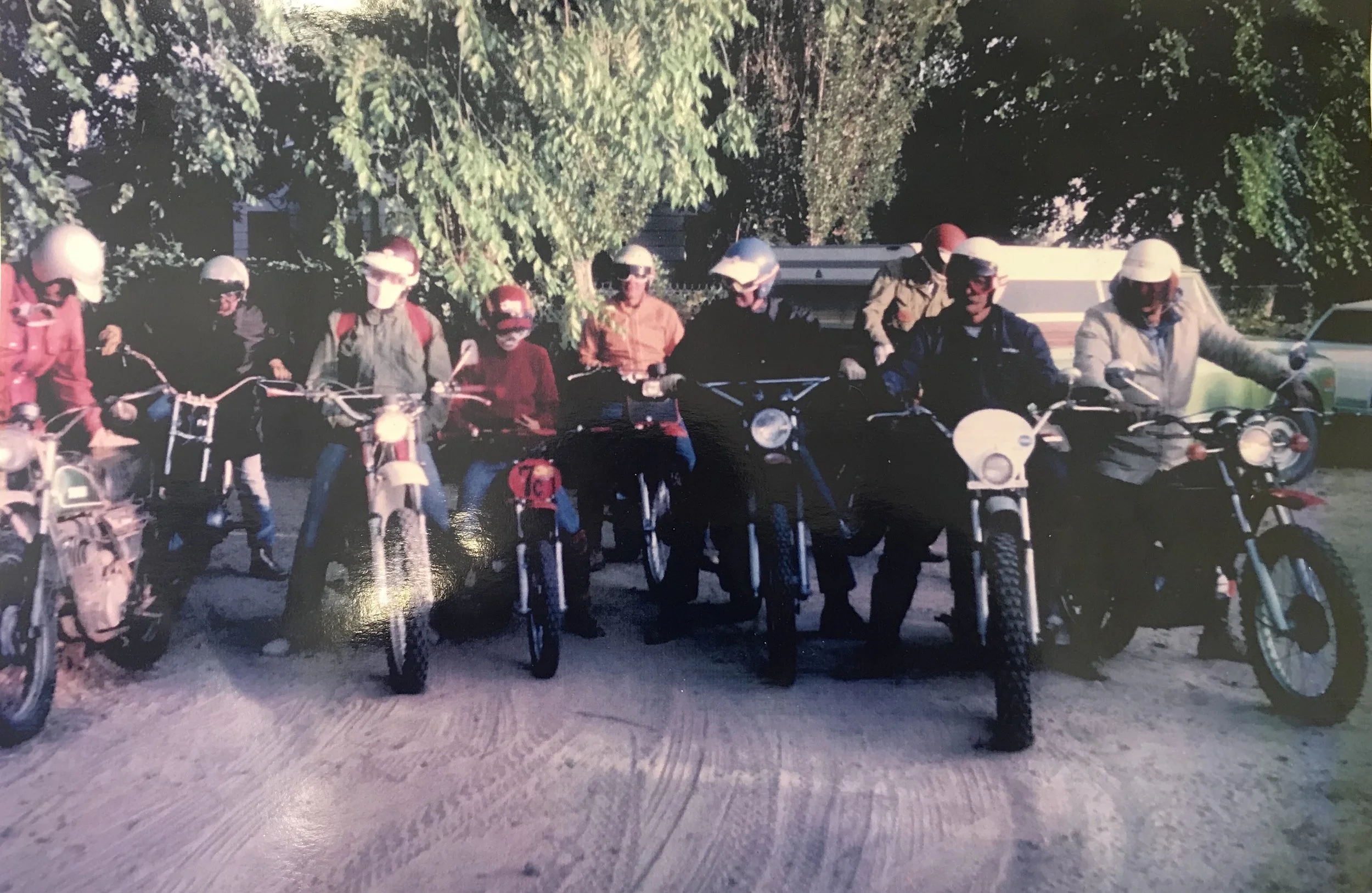

The author (No. 7C) prepares to join the grown-ups on an early edition of the Llano to Isabella. (Nancy Jonnum photo)

As I grew old enough to recognize that the event wasn't quite as significant as I’d previously imagined, I did what I could to actually make it so, arranging a makeshift pit area in our horse corral and fashioning a start-line banner by painting LLANO - ISABELLA on an old bed sheet and stringing it above the gate. I advanced to a plated XR200R at age 15, but I still had to wait for my driver license to complete the last section, by which point my interests were tending more toward high-school sports and my budding racing hobby. By the time I headed off to college, my occasional participation in the Llano to Isabella had come full circle, as I served as pit captain in what turned out to be the final edition. Any chance of a revival disappeared when my parents moved out of the desert following their retirements, and even our once-familiar tales from past editions of the ride were in peril due to the relative rarity of get-togethers with my dad's old crew—several of whom are now lost to the land where all the trails are perfect.

Late last year, I found myself alone for the holidays when I was unable to join my wife and daughter on a holiday trip to Italy with my in-laws, and as is sometimes the case in such situations, I was feeling somewhat nostalgic. For some reason, the Llano to Isabella came to mind, and I made a spur-of-the-moment decision to do a solo attempt at recreating the ride aboard my Africa Twin. After some late-night planning (with some help from Garmin BaseCamp and Rever), I awoke pre-dawn on Christmas Eve and braved the frigid freeway slog out to our old house, which I hadn’t visited in a couple of decades. Its sorry state didn't match my idyllic childhood memories, nor did my halting progress along the route's early miles, which now seemed to be a tour of meth labs and fence-blocked trails.

After refueling at Kramer Junction, I finally hit pay dirt in the form of a flowy two-track paralleling Highway 395, which I remembered as a reliable favorite from the past. Next was a side trip to the Husky Memorial (a site that wasn't on the original route but that I'd always meant to visit), followed by a surreal crossing of Cutteback Dry Lake and a pit for fuel and a snack in Randsburg. Now well behind schedule, I nevertheless decided to press on, heading through Fiddler Gulch toward Garlock. After two more forced detours—one by a lower-than-expected railroad underpass, the other yet another barbed-wire fence—the shadows were getting long as I hit another highlight: a twisty, technical jeep road over the El Paso Mountains.

I concluded it was somehow appropriate that my Llano to Isabella would be ending as it had so many times in the past—prematurely, at Red Rock Canyon—but I was bordering on melancholy at the prospect of a lonely night in the desert. However, as I pulled up to the visitors’ center at Ricardo Campground with the sun setting behind the picturesque cliffs, I had to rub my eyes at the sight of a pair of motorcycle-mounted Santa Clauses. Michael and Adam were honoring a new tradition of their own—an annual holiday California adventure ride in red suits—and they generously shared their campsite, their campfire, and their attention as I regaled them with tales of past adventures with Dad's lost gang.

Llano to Isabella lives on.

How a French Barber Saved Team USA

In 2000, sending an overseas email wasn't always an easy proposition, even when it included a story from the world's most important motocross race.

The Motocross of Nations happens this weekend, and as Jonnum Media’s own Mandie Fonteyn sets up in England to support Cole Seely and Team USA, I’m reminded of the one time I attended the event, covering the 2000 edition in St. Jean D’Angely for Cycle News.

Those were still the glory years of print moto-journalism, when we would publish exhaustive race reports in the newspaper every week. With AMA Nationals on Sundays and deadlines early Monday mornings, there was never enough writing time. In an effort to get in a couple hours' sleep on Sunday nights, I would typically complete chunks of the article during race day, before the motos were even finished, then add a lead and conclusion that evening before going back through the piece one last time, making any necessary changes, and sending it all back to the office in Southern California. The internet was still relatively young, and not much of my valuable time was devoted to web posts, which were usually limited to brief recaps that I banged out in a few minutes after the checkered flag fell.

This time though, then-editor Paul Carruthers had asked me to post some good website content during the course of the weekend, which would mean delaying most of the work on the print story until the race was actually completed. Fortunately, the time difference between France and California bought me nine extra hours, and I intended to capitalize by getting some quality sleep and then waking up fresh on Monday to write the bulk of that article in the hotel.

Back then you couldn't count on having an internet connection in your room, particularly in rural France, but after confirming that the MC Motocross Circuit pressroom would be open on Monday, I confidently put my plan into action. On Saturday I scored interviews with Team USA riders Ricky Carmichael, Travis Pastrana, and Ryan Hughes, as well as team manager Roger DeCoster, and my web content did justice to the squad’s dominating performance in qualifying. I even earned a compliment from my photographer, the late, great Steve Bruhn (an internet pioneer in the moto world).

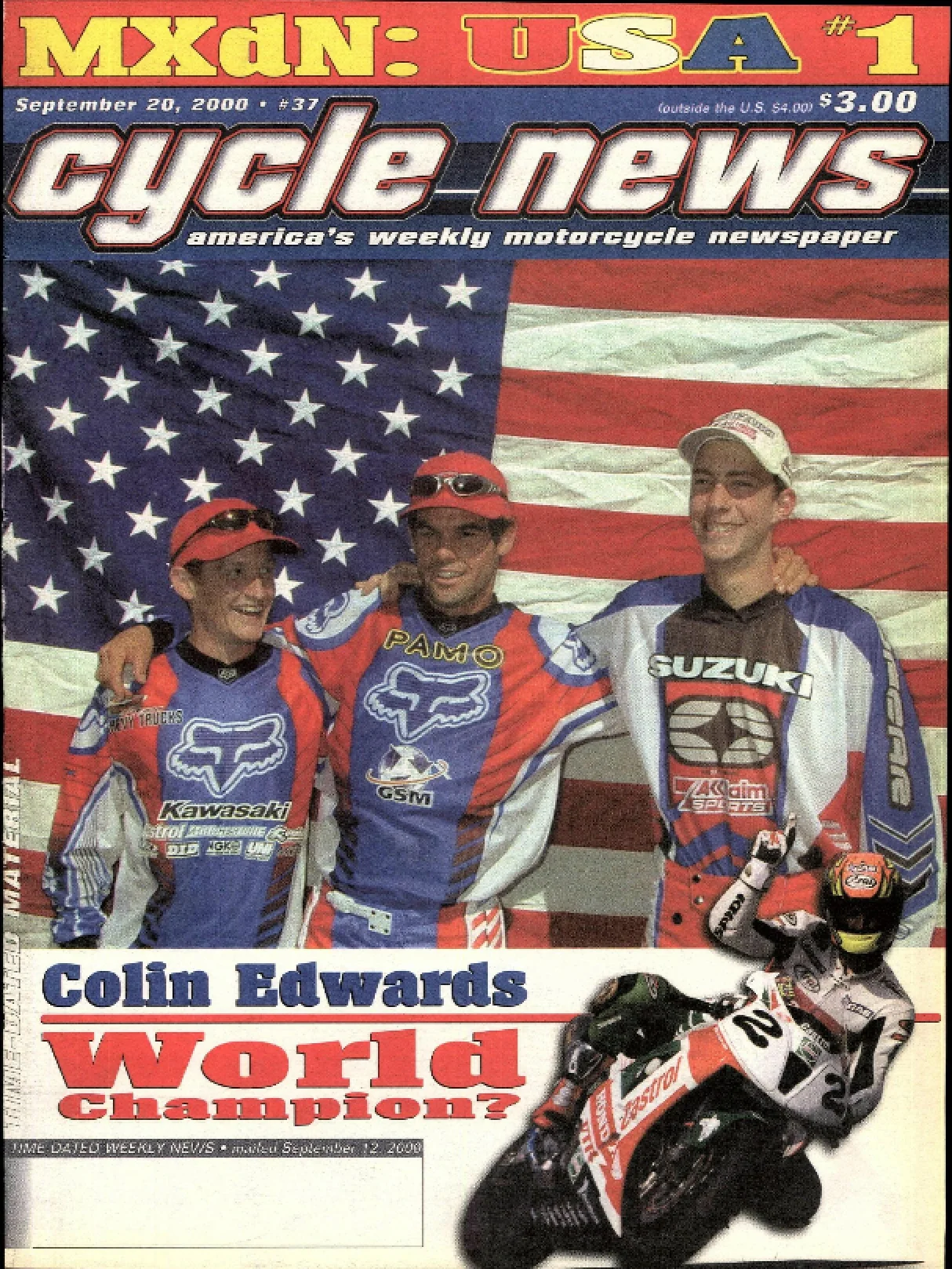

The 2000 MXdN Cycle News cover story that very nearly wasn't. Steve Bruhn photo

The friendly banter wasn't limited to fellow countrymen; while journalists clearly pulled for their respective countries, they willingly worked alongside reporters from other nations, even helping each other out by providing background on their teams. Similarly, because riders based out of their sponsoring manufacturers’ trucks, mechanics for the PAMO Honda squad, for example, spun wrenches on the CR500s of both Hughes and Frederic Bolley, arguably Team USA’s most formidable rival.

In fact, when Team USA posted a convincing victory the next day, it was thanks not only to Hughes’ and Carmichael’s outright moto wins, but to Bolley having his nose broken by an errant rock in the early laps of the first moto, yet while DeCoster accepted the Chamberlain trophy on the podium, press officer Pascal Haudiquert—a proud Frenchie—graciously offered me his congratulations.

Pleased that my country had snapped what at that time was an unheard-off three-year winless streak, and proud with having populated CycleNews.com with a steady stream of stories, perspectives, and images, I fired out a last web post before celebrating with a belly-full of oysters and Muscadet wine, then drifting off to a luxurious (and rare) Sunday-night slumber.

As planned, I awoke before dawn and spent the morning knocking out nearly 5,000 words for the print edition, including ample quotes, three sidebars, half a page of news notes, and another half-page of agate. Finished with an hour to spare, I checked out of the hotel and headed to the track. Entering the now-abandoned pressroom, I plugged my laptop into the Ethernet port that had served me so well for the previous two days (Wi-Fi wasn't an option back then), only to discover that internet service had been disconnected the night before—a detail I had neglected to confirm earlier when making my plan. Sacrébleu!

If internet service was rare in French hotels at the turn of the millennium, it was even scarcer outside of them, and I knew immediately that my options were very limited. A janitor cleaning the pressroom told me of an internet café about 10 kilometers away, and I hightailed it in my rental car, heart racing as I made dangerous passes of tractors on narrow country roads. Not yet having even heard of GPS, I nonetheless managed to find the village using just the janitor’s sketchy directions, but I needed another 20 minutes to locate the internet café. When I did, I was horrified to learn that it was closed for a French holiday. Putain!

Imagining Carruthers sitting down at his desk to find an empty email inbox, I desperately began running down the village’s deserted sidewalks, tugging on doors of random businesses, not even sure what I would do should one of them open. When I spotted a man unlocking a hair salon, I hailed him and stuttered out my predicament in broken French, and despite my frantic appearance, he invited me in. Introducing himself as Hugo, he explained that he had stopped by his parlor to pick up a forgotten book to read on his day off, but he kindly invited me upstairs to his office. There, I saved my story onto a floppy disc and handed it over with trembling fingers, whereupon Hugo dutifully connected his PC via dial-up modem and emailed the story off to California from his personal account.

That week, as American race fans eagerly absorbed the details of Team USA valiantly vanquishing the home team, they had no way of knowing that the fact they weren’t looking at six blank pages was thanks only to the heroics of a French hair stylist named Hugo.

Midnight Run

His P11 having shed its rear tire in the middle of nowhere, the author's salvation depends on a nocturnal, high-desert steeplechase.

In “The Case of the Inverted ’Taco,” my mighty 1967 Norton P11 was the protagonist in a faceoff with a hapless little Bultaco Sherpa T, but over time the British steed’s power and weight began to be its undoing. As Southern California’s desert trails became increasingly rough during the mid-1970s, the Norton was having a hard time keeping up with its nimbler competition from Spain, Sweden, and Japan, and my efforts were resulting in an alarming number of pinched inner tubes. Seeing the writing on the wall, my older brother and riding partner Corky had elected to stop racing his own P11 and had instead begun to serve as my pit captain.

In one particularly long District 37 enduro that started east of Lucerne Valley at Soggy Dry Lake, I was enjoying an overdue decent day on the trail until I arrived at the furthest point from the pits on the third and final loop, where the rocky terrain once again got the better of the Norton’s rear tire. I had been riding on a late minute, and by the time my Avon was unceremoniously emptied of air, the sun was already well into its descent. Lacking the tools for a repair and the patience to wait for the sweep crew, I made the questionable decision to leave the trail and head back toward camp cross-country, via dead reckoning.

The abused tire behaved just long enough to get me well and truly into the middle of nowhere, at which point it promptly came off the rim and became entangled to the point that I was forced to stop. I piled some rocks under the Norton's skid plate, removed the rear wheel, and wrestled the rubber out of the swingarm, then resumed riding on the bare rim until it eventually started to crack. It was now clear that I would soon be stranded, and the sun was beginning to slip behind the Granite Mountains. With my options close to depleted, I decided to throw in the towel while I was still on relatively high ground (a ridge overlooking a nearby lakebed) and propped the Norton against a boulder.

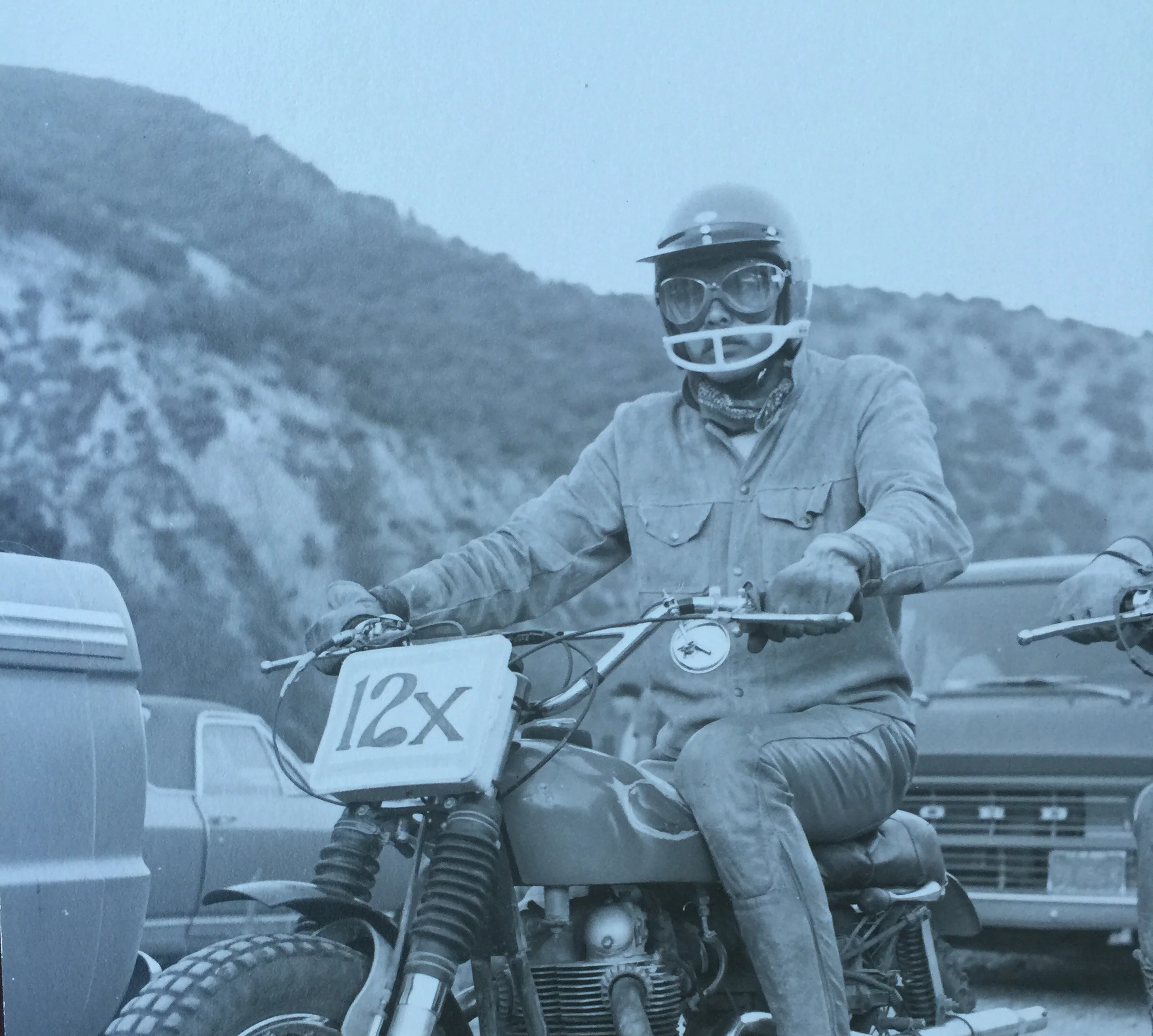

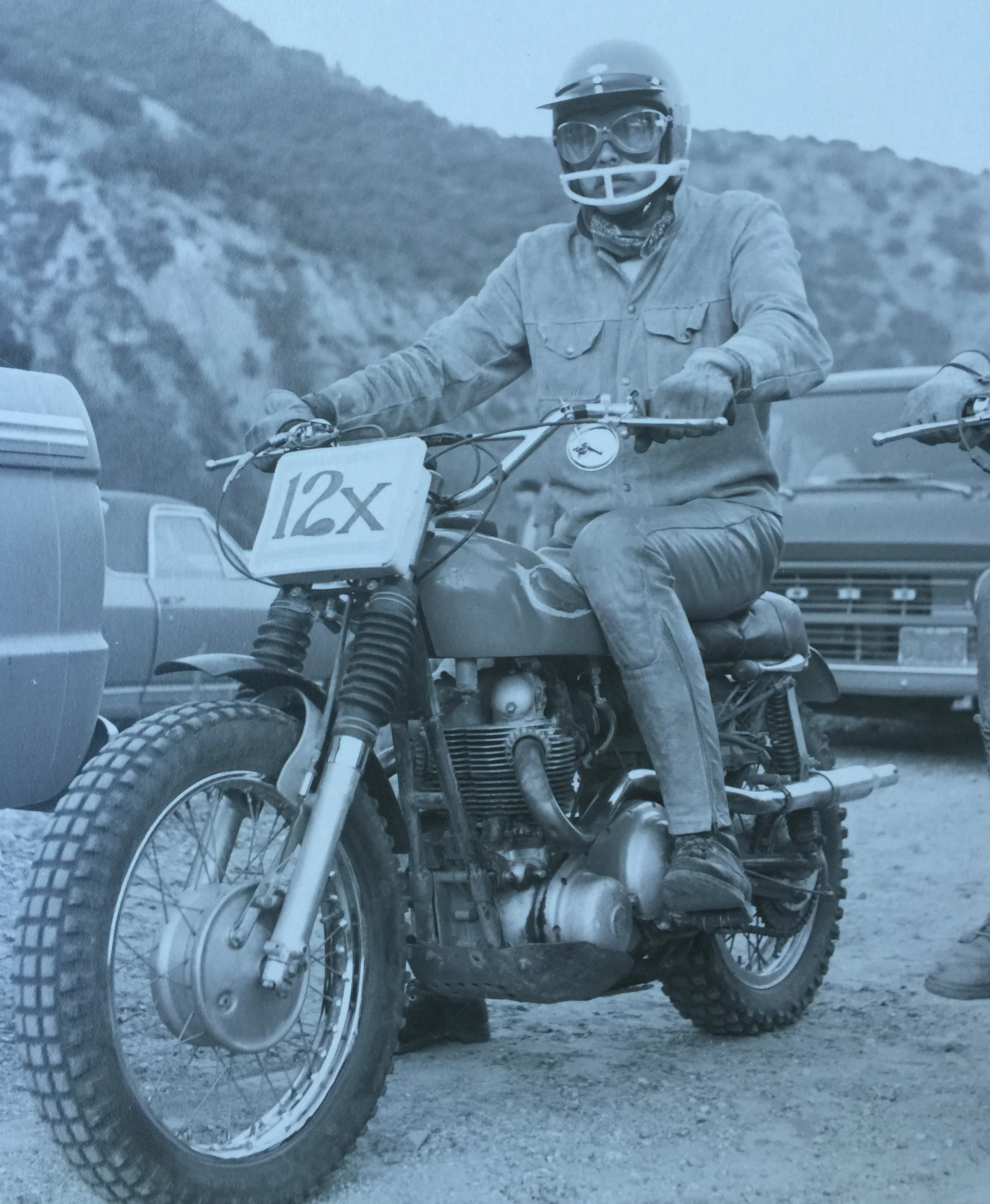

The author prepares to start an enduro aboard his P11, both tires valiantly holding air for the time being.

As the final minutes of sunlight slipped away, I began clearing rocks from a flat spot next to the wounded P11, buttoned my riding jacket up to the neck, pulled my bandana over my nose like a bandit, and prepared to spend a chilly night in the desert. As I stretched out on my makeshift bed, trying to convince myself that it wasn't all that uncomfortable, something made me look up, and my heart skipped a beat when I saw a pair of distant headlights cutting through the night.

Blinking, I surmised that the vehicle belonging to those twin beams was driving across the adjacent expanse in my general direction! Moments later, I was hit by another, less comforting insight: “my general direction” wouldn't be good enough; even the degree or two that the unknown driver was off could be enough to thwart my salvation unless I took immediate action.

I scrambled to my feet and set off down the hill at a dead sprint, dodging like a running back as boulders and creosote bushes emerged from the surrounding blackness. After initially waving my arms and yelling at the top of my lungs as I ran, I noted that the vehicle’s pace and path were continuing unchecked and decided I was better off directing all of my rapidly dissipating energy to my nocturnal steeplechase.

The vehicle was moving at a brisk clip, and as I hit the base of the slope and set out galumphing across clear, level ground, I quickly ran some mental geometry and judged my chances of intersecting its path in time to be about 50/50. In order for the angle on which I had settled to work, the driver mustn’t increase his speed, nor must my own pace ebb.

Already my velocity was in jeopardy of flagging, my athletic performance restricted by heavy leather riding pants and boots. On the other hand, I was hardly lacking for inspiration, so while I no doubt cut a less-than-graceful figure, and my breath was now coming in desperate gasps, I arrived just in the nick of time, bursting into the periphery of the headlight beams at the final possible second and—with the last of my energy reserves—mustering a final spasm of bellowing and gesticulation.

The startled driver slammed his brakes, and when he opened the door to see why a freak was unexpectedly splayed, panting, on his pickup truck’s hood, the interior light illuminated his face. Amazed, I saw that it was Corky, who had faithfully taken up the hopeless hunt after I failed to turn up back at camp. After I had caught my breath, Corky and I used a flashlight to find the abandoned Norton and roll it to the truck. Back at our camp trailer a couple hours later, I appreciatively climbed into my sleeping bag and drifted off to sleep, my slumber visited by dreams of brand-new open-class Japanese thumpers being rolled into my garage.

The father of Jonnum Media founder Chris Jonnum, Jerry is a lifelong motorcycle enthusiast and former amateur off-road racer. Have a Moto Story you'd like help telling for free? Email chris@jonnummedia.com.

A Morning at K-Tree

Seeking the ultimate motorcycle-race spectating experience? Look no further than Conker Fields' K-Tree at the Isle of Man TT.

The best decisions are always born in a bar. So there I sat, just under a year ago, pint in hand at the top of The Triangle circuit on the balcony of The Tides in Portrush. Michael Dunlop, Ian Hutchinson, and Michael Rutter were screaming down Black Hill, duking it out and drafting one another for the lead of the North West 200, when my mate Mark looked at me and declared, “We’re going to the TT.” Hops, barley, a roomful of rabid fans, and the sound of superbike exhausts reverbing off of the homes and hedgerows of Northern Ireland may have lead to a snap judgment. I nodded my head and we clinked glasses. It will stand as the best decision I’ve ever made.

Mark and I recount this story amongst a pack of likeminded fans filling a plot of land near the 22nd milestone of the 37.733-mile road racing mecca. Many of them smile knowingly and welcome us to their fold. Conker Fields, as it’s called, is a popular spot for those in the know because this section of roadway is highlighted by something called K-Tree. Literally a tree with a white “K” spray-painted on it, K-Tree marks a left kink at the bottom of a small decline that immediately follows a high-speed, rising right. It’s rumored to make for some hairy visuals. At the moment it’s plugged with fans trying to get where they need to be. Most around us are enjoying lunch or queuing up for tea at a makeshift hospitality tent, while others still are jockeying for prime positions as close to the road as possible—smartphones, GoPros and SLRs at the ready—getting ready to capture the action. That’s where we are. Pressed up against barbed wire, listening to stories of TT history and sharing how a Canuck ended up here with his Northern Irish buddy.

The roads of the Snaefell Mountain Course will be closed to public traffic soon enough, and the narrow, two-way streets will all run clockwise. We rode up here with little time to spare, and the corner marshals are already in position. Unlike at closed circuits, the silence of this empty course serves to spike adrenalin and prick up ears. The Course Inspection Subaru WRX STi is the first to rouse attentions as it womps by. It’s moving pretty damned quick, or at least that’s what I initially think, from two yards away. Minutes later, the first bike appears: a Fireblade SP (CBR1000RR) piloted by the track marshal in full day-glow orange, it makes the Subie look like it was standing still. The audience oohs, ahhs and we all do a gut check. Given his pace, we’re about 20 minutes from the first pack ripping through. I swap lenses on my rig and go through the motions of following an invisible bike through the route. Every hair on my body begins to stand at attention. A husband-and-wife team of 20-year veterans beside me bickers in heavy Scouse about whose turn it is to roll a smoke, barely batting an eye.

A sunny day Conker Fields... not a bad setting to take in a motorcycle race. Neundorf photo

The Snaefell Mountain Course is legendary. For 110 years, riders have tested mettle with metal in the pursuit of speed and glory. Two days ago, we gave it a run of our own. Thumbing our bikes to life in the belly of our overnight ferry at Douglas Harbour, we quickly disembarked to find the start/finish straight. Of course so did thousands of other riders. To say our pace was less than blistering would be an understatement. There was traffic everywhere, and the cops had set themselves up every five miles or so. Even still, I wouldn’t have the stones to warp a throttle-stop around here. The streets are incredibly narrow, there’s no shoulder to run off on, and undulations of all sizes are scattered amongst almost every one of the 264 turns. Fog on the mountain section was thick, too—even by English standards—so we kept things civilized. We clocked in at around 50 minutes… or 33 minutes slower than Michael Dunlop’s record-setting 133.963 mph average from last year.

My neighbors at the hedge snuff their third consecutive hand-rolled fag and finally take to their feet. Almost instantly, as if on cue, the howl of a tortured V4 and the scream from an inline unit can be heard through the trees. Within seconds Bruce Anstey and David Johnson are near touching leathers as Anstey’s Honda has clawed back the 10-second start gap from Johnson’s Norton. They quite literally blast by us. The arms gripping phones and GoPros retreat like horizontal dominos, and the hedges move with metachronal rhythm in the wake of the bikes. The force of the sliced and displaced air prompts me to flip my cap around before the next twosome goes by; nobody needs it flying off onto the road. All I can do is laugh. The second group warps past. All any of us along those hedges can do is laugh.

The bikes are hitting speeds near 150 mph through this section of turns. At this distance—roughly 3-feet—they’re a blur of color and sound. I can’t stop giggling. We move down the road a touch, closer to K-Tree, to get a more expansive view of the section. Seeing front ends aloft and front tires cocked, I’m gobsmacked by the ability, courage, and trust in rubber the riders must possess to pivot a unicycle at over 150 mph just inches from stone walls. It’s like watching the intricacies of open-heart surgery, tackled with a chainsaw. This is fucking nuts.

I’ve been up close and personal at multiple MotoGP events. I’ve watched in awe from behind Armco as a Sykes, Rea and Davies lead a pack plunging through the Corkscrew. I’ve clocked over 170 mph myself on the back straight of COTA, and I’ve poured over countless hours of TT footage on YouTube. None of it—I mean none of it—prepares you. Regardless of where you sit, the Isle of Man TT delivers the most exciting and exacting riding you’ll ever see. There’s a ferry ticket with my name on it for next year’s races. It was booked before we even left. Should you need some more convincing to join me, meet me at a bar and we’ll work on your decision-making.

It took almost 20 years for the moto bug to bite but ever since, Matthew Neundorf has been sussing out ways to work riding and motorcycles into everything he does. Working as a freelancer, in between days inspecting construction sites in Toronto, Matt has handled the bulk of motorcycle coverage on Gear Patrol and helms a weekly column on Bike Exif. Thanks to some incredible experiences through Baja, British Columbia, Eastern Oregon, and the south coast of Spain to name a few, the world of two wheels now has him constantly seeking out excuses to test and improve the limits of his riding abilities on all sorts of terrain in every corner of this world. Follow Matt on Twitter and Instagram.

An International Love Story

A young lady gets a crash course in adventure riding--and motorcycle maintenance--on an epic Latin American road trip.

Not being the type of person who truly comprehends the meaning of “crazy” or “impossible,” I delighted in a self-realized moment of genius: trading a backpack for a motorcycle to circumnavigate the South American continent. The only hiccup was that, well… I had never ridden a motorcycle. The two-day MSF Beginner Rider Course coupled with reading Motorcycling for Dummies cover to cover (twice) was my crash course in two-wheeled preparedness. On paper the DMV said I could ride a motorcycle, but in reality I had the sum total of eight hours’ experience in the relative safety of an empty college parking lot.

Landing in Quito, Ecuador, my first order of business was to, you know… buy a motorcycle. I did not, however, arrive with an inkling of which motorcycle to buy. After challenging that question by dropping a surprisingly tall KLR and a BMW that didn’t appreciate my zealous handful of front brake on a banked uphill curve, I found the answer to be simple: one that doesn’t hurt much when you wear it, and that can be picked up afterward. I settled on a 2006 Honda XL200, a street-legal dual sport that moonlighted as the local police bike.

With a top box, two kayak dry bags, and a tangle of bungee cords, I wholly embraced being ringmaster of my very own traveling shit show. Once I successfully navigated myself out of major cities (a few times with the help of a taxi), traffic dissipated and I was left to serenely contemplate my life in relative silence, only occasionally interrupted by packs of rabid dogs, wandering llamas, VW Beetle-swallowing potholes, and cliff edges made daunting by gusty winds. There was also another kind of silence: the painfully awkward, gas-gauge-flickering variety. The first occurrence was unexpectedly in the middle of the Sechura Desert of Northern Peru, where I prayed that the generous gas gods would send me an entrepreneurial villager with a plastic five-gallon bucket of fuel. (They did.)

Somewhere outside of Cusco, I found myself alone again (in silence) on a gravel-packed road with a dead bike; only this time the issue appeared to be the ominously dangling chain, its tacky, half-greased surface catching souvenirs in the dirt. Armed with only the under-seat tool kit, I somehow managed to loosen the large chain-tensioning bolt with the basic five-inch tool, my boot, and an explosion of profanity. While I stayed in Arequipa for a few days to explore on foot, I decided it was long overdue I treat the lady to some quality time with a real mechanic. Not being able to read the manual, which had been printed in Brazilian Portuguese, I guess I overshot my first oil change by an itty bit. There was plenty of time for the mechanic to scream at me in Spanish (while what looked like high-viscosity Turkish coffee trickled from the drain hole), informing me that it was once per 1,000 kilometers (not every 3,500). At the very least, the educational earful wasn’t a total loss and I learned how (and how often) to change my oil. That’s progress.

The author and her XL200 on a highway somewhere in Argentina. Photo courtesy of Farrell

When I crossed the Southern Andes between Chile and Argentina in the shadow of Aconcagua (South America’s Everest), I miscalculated how much gas was required to complete the mission, despite departing with a full tank and riding with a one-gallon, gas-filled plastic bottle as a backrest. I was a quick study in figuring out that neutral was my friend while descending 10,500 feet of hairpin switchbacks over Los Caracoles Pass (aka the most dangerous road in Chile), hoping to find a functioning gas station somewhere near the bottom. (There was, and the proprietor was treated to a happy dance of disbelief and overwhelming gratitude.)

The little Honda that could threw me a few curveballs, and deservedly so, as I had become keenly aware of high-altitude/oxygen-starved starts at 12,500 feet in Puno, Peru, the heart-stopping noise of a dead battery at night outside Rio, and the rim-deforming effects of hitting a pothole at speed on a desolate Venezuelan road that could’ve easily doubled as the cratered surface of the moon. I learned that inevitably, when left to my own devices, I found a way to persevere… and that roadside auto mechanics in Venezuela are neither motorcycle savvy nor gentle with a hammer. When the mechanic announced he was finished with the front wheel while clutching a handful of leftover parts, I made the bold move to install the rear tire myself. By this time, death felt like a foregone conclusion, so might as well be at my own hand.

With only a few international incidents, a city-leveling earthquake, and gluttonous consumption of asado, empanadas, tropical fruit, Malbec, and gelato under my belt, the journey was nearly over as I pulled up to the Suzuki Superstore in Medellin. It was here that my little Honda had her final servicing before I regretfully sold her upon my return to Quito. The business owner explained to me that he was a lifelong Suzuki enthusiast, but after my service, he would preach the good word of Honda.

“How many kilometers has it been since you cleaned your air filter?”

“Ummm… 42,000?”

“That’s crazy! It’s damn near impossible for a motorcycle to keep running with an air filter this dirty. All you needed to do was clean it with a little diesel.”

“Hmmph…good to know.”

Ten years and 100,000 miles after her first foray into motorcycling, Cristi Farrell is an intermittent motorcycle industry freelancer when not chained to her desk as a California-licensed geologist with a local consulting firm. An unquenchable thirst for wanderlust and a passion for motorcycling fuel off the beaten path adventures like chasing fireflies and dodging tigers after dark on an Enfield Bullet in Bardia National Park, getting lost in the deserts of Rajasthan on a Triumph Bonneville, and using a Honda XR250 as a ladder to pick fresh dates in the Dades Valley. She has contributed to and reviewed motorcycles for a variety of publications including American Motorcyclist, Revzilla's Common Tread, Cycle News, and Motorcyclist, and is a co-host of the Moterrific podcast.

The Water Boy’s Water Boy

11-time Baja 1000 winner Johnny Campbell remembers getting some unofficial assistance from Robby Gordon during the 2013 Dakar Rally

No one finishes the Dakar Rally without support in some way, shape, or form, and you get it wherever you can find it. My first experience in the event was back in 2001, when it took place in Europe and Africa. I was a privateer, but I was supported by Italian Honda importer Dall’Ara Moto (who prepared my Honda XR650R) and Acerbis owner Franco Acerbis (who sponsored me).

By the time I returned to the event, for the 2012 edition, it was taking place in South America, and I was the navigator for Robby Gordon. Although this time it was my role to provide support, I learned a lot riding in the seat with a great American off-road driver (though there were certainly a few scary moments!).

The following year, I was back on a bike, as HRC had decided to embark on their Dakar project and had hired me to help develop the machine. I was over 40 years old and hadn’t intended to race at that point in my career, but I stepped in after a series of injuries with some of our riders. Although I was entered as a competitor, my primary job was to be a “water boy,” providing support for my teammates Helder Rodrigues and Javier Pizzolito in whatever way I could. If they broke down, I was supposed to sacrifice my results and scavenge needed parts from my own equipment to make sure they could carry on. I was fine with that, but of course there was no water boy for me—at least not officially.

HRC was treating that edition as a big learning opportunity, to gather data on the bike—a CRF450X-based chassis and engine with factory fuel injection and a complex fuel system with five different fuel tanks. We wanted to see how we stacked up against the other equipment and establish a baseline to develop what would eventually become the current factory CRF450 Rally.

The early stages were held in Peru, and a few days into the race, my bike started having a bad engine hesitation shortly after the start in Pisco, like it was starving for fuel. I tried continuing for a while, but the bike was borderline unrideable, and I knew I had over 300 kilometers to go and that we were headed into some big sand dunes. Rather than risk getting stranded too far in, I stopped after about 20 kilometers to check things out. Based on a superficial inspection, everything appeared to be fine—the plugs were okay and the tanks had fuel. I figured it must be something more significant, but while I had plenty of tools (I was a water boy, after all), I didn't have any spare parts to speak of.

After racking my brain for a few minutes, I came up with an idea. I knew that the cars hadn’t started the stage yet, so I pulled out my satellite phone and called our support people, who were preparing to depart the bivouac for the stage’s finish in Nazca. “Hey,” I said, “go find Robby Gordon and give him a fuel pump and an ECU—anything you can think of that might be causing the problem.”

The team rounded up the parts and brought them to Robby and explained the situation. “No problem!” he said. “Anything for Johnny.” He and his navigator, Kellon Walsh, put the stuff in their car and left when their time came up.

I had to wait quite a while, but in the meantime I was able to get all the necessary components stripped off of my bike so I was ready to immediately begin installing the replacement parts when I received them. Eventually, Robby arrived, and he was easy to spot in his bright-orange Hummer. When he saw me waving him down, he spun a big U-turn, threw the care package out the window and took off, and I dug the stuff out of the sand and went to work putting my bike back together.

By the time I completed the work (still unsure if the problem had been resolved), all the cars had already passed and even some of the first trucks were coming through. I lost so much time, but I wasn't really racing for position anyway. I got going, and although the bike started hiccupping again toward the end of the stage, I made it to the day’s finish and eventually completed the race. Come to think of it, the guys never did tell me what the problem had been.

That was my last Dakar on a bike, although I did return two years later, again as a navigator for Robby, who this time was entered in the “Gordini,” a two-wheel-drive FIA truck that he built. Based on the machine Robby raced in the Stadium Super Trucks series, the HST (as it was officially called) was much smaller than his Hummer, and the space was pretty tight for the passenger. Fortunately, we didn't have to squeeze any spare fuel pumps in the cab that year…

Campbell is an 11-time winner of the Baja 1000, and currently owns and operates JCR Racing, American Honda's official effort for GNCC, NHHA, and WORCS racing. Have a Moto Story you want help telling for free? Email chris@jonnummedia.com.

An Italian in Baja

Repsol Honda MotoGP Team Manager Livio Suppo recalls riding in Baja, Mexico, as a participant in the inaugural Camel Trophy Bike.

Since I was very young, I always had a great passion for motorcycles, but it took years to convince my father to buy me a bike. He finally relented when I was 11, but although my sole thought from that point on was racing off-road, my family wasn't as enthusiastic. My only option was to use my own weekly allowance to race, so with almost zero budget, I was limited to the regional enduro championship near my home in Turin, Italy. I never had any great results, but I was able to take part in some of the races.

One day when I was a 23-year-old university student in 1987, I was reading an issue of Moto Sprint (the Italian weekly racing magazine), and I happened across a coupon to try out for an expedition-style off-road event. Started in 1980, the Camel Trophy was a competition between national teams driving Land Rovers, usually in South America or Africa. From the coupon, I learned that Camel Italy, in cooperation with Honda Italy, was planning to introduce a two-wheel version called the Camel Trophy Bike, in part to launch a then-new Honda model called the Dominator (NX650 in the U.S.).

At the time, the four-wheel Camel Trophy was huge in Europe, thanks in part to the success of the Dakar Rally, and I couldn't imagine ever getting to participate. Nonetheless, I decided to fill out the coupon. The perception from the outside was that the Camel Trophy was a pure competition like the Dakar, but in reality it was primarily a promotional event. A series of regional tryouts were held around Italy, and I participated in one at Arsago Seprio, north of Milan. Eventually, I was named among the 10 finalists who in December were sent to the Motor Show, a trade show in Bologna, where we were evaluated in riding tests aboard MTX125s, but also in running races, English speaking, interviews—even a psychological exam!

Livio Suppo (right) with teammate Claudio Foschini on El Diablo dry lake near San Felipe, in Baja, Mexico. Photo by Scott Cox / Resmarket

When all was said and done, I was elated to be selected as one of the two official team members, along with Claudio Foschini, a motocrosser who was 7 years my senior. For sure there were other riders who were faster, but maybe I spoke better English than they did or did better in the interviews—I like to joke that I was lucky to have blue eyes!

When the time came, we flew to California and went to American Honda’s offices in Los Angeles. There, Claudio and I climbed on our Dominators and, accompanied by the Camel Trophy entourage, headed south to the Mexican border, where we crossed over and rode a big loop in Baja. Honestly, it was more of a long tour than a competition, although the format did have us taking part in the Gran Carrera Internacional, a real desert race similar to the Baja 1000—but while everyone else was on 500cc two-stroke motocrossers, we were on our Dominator dual-sport bikes! The course was 1,500 miles long, routing us through Tijuana, Ensenada, San Felipe, Mexicali, and the Glamis sand dunes.

It was a lot of fun, and the Camel Trophy organizers would go on to hold other editions in South America and Africa, although that debut ’88 event was the only time I participated. It was an amazing two weeks that I’ll never forget—my first time in the U.S., and the only occasion I ever had to be a sort of factory rider. Beyond that though, the experience changed my life, as I had the opportunity to meet several people who had a big influence on me: Italian journalists who were traveling with us, Camel P.R. man Francesco Rapisarda (who I went on to work with at Ducati), Honda representative Carlo Fiorani (who I work with now), and Gabriele Mazzarolo, now the owner of Alpinestars and still a good friend. I remember one night we all went out to dinner with Roger De Coster, who was a myth to me. I also met a number of Americans, including marketer/photographer Scott Cox (who was the event's American promoter) and Don Ogilvie. Father of the late Bruce Ogilvie (a talented desert racer who built the effort behind American Honda’s legendary successes in the Baja 1000), Don made a big impression on me by riding much of the course with us at age 62.

Many of those connections, along with my university degree in economics and marketing, which I earned a year later, helped to kick-start my career, and I often gratefully think back to the day when—almost on a whim—I decided to send in that coupon.

Suppo is the Team Principal and Communications and Marketing Director for the Repsol Honda MotoGP team. Have a Moto Story you'd like help telling for free? Email chris@jonnummedia.com

Blendzall Barbecue

Hard lessons about premixing fuel with the author's first two-stroke.

When I was a kid, my family had a Honda CT Mini Trail 70 that I’d ride after school almost every day. The thing sipped fuel, so after topping off the tank from a gallon milk jug that my dad would leave in the garage, I’d ride the little four-stroke until the sun went down.

Finally, after years of begging, my dad relented and bought me my first real bike for my 15th birthday—a brand-new 1975 Honda Elsinore CR125M. I couldn’t believe it—the happiest kid in the world! Along with the bike, he gave me several pint-bottles of Blendzall Racing Castor (although I still didn’t have a real fuel can), and he explained that since my new ride was a two-stroke, it was extremely important that I mix the fuel before starting the engine.

As you can imagine, I was more eager to ride than ever when I got home from school the next day, but I wasn't sure what the 40:1 instructions on the Blendzall bottles meant. My dad hadn’t returned home from work yet, so I walked next-door to the house of my neighbor, who was tying on an apron and donning a chef’s hat as he prepared to cook an early barbecue dinner for his family. While his curious children gathered around, he sat down his spatula and examined the yellow bottle I handed him, carefully reading the label.

“Hmmm, let's see,” he muttered, running mental calculations for a minute or so. “That works out to one bottle to a can of gas.”

I thanked him and returned home to our garage and--still unaware that normal gas cans had a 5 gallon capacity--poured the bottle into my 1 gallon jug. Next I emptied that into the shiny silver tank of the new Elsinore and, after strapping on my helmet, rolled the bike into my backyard, pulled out the start lever and gave it a healthy kick. The engine fired up immediately and ran fine for a few seconds before it began burbling and bogging, and then died completely. Perplexed, I pulled out the lever again, and although the mill was less willing to start this time around, it fired up after 30 or so determined kicks. Uncertain as to why my mighty new motocrosser was so reluctant to idle, I heartily twisted the throttle, the silencer emitting a strangled exhaust note—gah-ding, gah-ding, gah-gag, gah-ding, gawwwwww—along with a huge cloud of blue fog that floated gently across the lawn and over our wooden fence, mingling with the smoke from the neighbor’s Weber.

If a little is good, shouldn't a lot be even better?

Just when I was beginning to think that my dad had purchased a lemon, the Honda’s engine started to sound like it was going to clear out: Rrrrrrrrrrrrrrruuuuuhhhh…. Encouraged, I held the throttle to the stops, put the bike in gear and slowly let out the clutch lever: Ba-dong, ba-dang, ba-dong, ba-ding, ba-DING, BA-DING, BRAAAAAAHHHHH!! In an instant, the engine cleared out completely and came onto its powerband which, as you might imagine, was rather more savage than that of the CT70 to which I was accustomed. With me hanging off the rear fender for dear life, the bike took off across our yard, my legs trailing behind and my right wrist in full whisky-throttle mode.

When I opened my eyes, I saw that I was headed straight toward the aforementioned wooden fence, through which my bike proceeded to put an Elsinore-shaped hole while the slats cleaned me entirely off the seat. Previously reluctant to run, the crashed Honda now refused to quit, burning donuts into the lawn as it spun around the right grip, sending children diving for cover while my neighbor made a valiant attempt to shield his tray of hamburgers from the barrage of flying turf.

The next day, my dad brought home a follow-up birthday present: a new Ratio-Right measuring cup.

Now a pro with a Ratio-Rite, Forrest is an advertising sales manager for Transworld Motocross. Have a Moto Story you'd like help telling for free? Email chris@jonnummedia.com

The Zombie Hat Chase

"I was to translate for Rossi’s teammate, American Nicky Hayden... which made my current scenario—stumbling on protesting legs, across the Ducati campus from the studio where the event was set to kick off in minutes—somewhat inconvenient."

Pretty much everybody has had that nightmare where you feel as though you're running through Jell-O, body unable to execute the mind’s desperate pleas to sprint. One day in March of 2012, I found myself experiencing that scenario in real life, lurching down the corridors of Ducati’s Borgo Panigale headquarters like a character from Night of the Living Dead while my brain frantically urged my protesting limbs to turn over. "Chris, where are you?!" my boss's voice boomed through my cell phone. "We're about to start!"

The occasion was the Ducati Team’s 2012 pre-MotoGP season unveiling of the Desmosedici GP12, although the actual team launch had already taken place two months earlier at the gala event known as Wrooom. Once held every January at the Madonna di Campiglio ski resort in the Dolomite region of the Italian Alps, Wrooom was always a golden ticket for journalists, who were fêted for an entire week, with extended sessions of skiing, snowboarding, wining and dining only occasionally interrupted by the odd press conference.

The journalists’ workload for that year’s edition had been particularly light, as the traditional motorcycle unveiling was cut from the program. That move was prompted by then-Ducati Corse boss Filippo Preziosi’s attempt to improve chassis performance following Valentino Rossi’s disastrous 2011 Ducati debut, but while the motivation was laudable, the unveiling’s cancelation gave the event an anticlimactic feel—rather awkward for me as the team’s press officer. It was vital that this new, additional launch be a success.

Valentino and Nicky--both safely behatted--at the 2012 Desmosedici unveiling. (Milagro photo)

Goodness knows enough work had gone into the preparation. Team sponsor TIM (owned by telecommunications company Telecom Italia) was set to livestream the event through their Facebook page--still a relatively ambitious idea back then--and Ducati's marketing department had performed its typically excellent promotional work. Fans were already logging on from around the world, and a select group of VIP guests (mostly executives from various team partners) was seated in the studio at that very moment. Famous Italian comedian Valerio Staffelli would be interviewing the riders on stage, and I was to translate for Rossi’s teammate, American Nicky Hayden. All of which made my current scenario—stumbling on protesting legs, across the Ducati campus from the studio where the event was set to kick off in minutes—somewhat inconvenient.

My body had been much more cooperative the day before, when I competed in the Rome Marathon, setting what is still my personal record over 26.2 miles. On the train ride back to Bologna that night though, my hamstrings began locking up.

“That was a bit more abusive than we were led to believe,” I could imagine my muscles saying. “Hope you’re not expecting much out of us tomorrow...””

At first, I had managed launch day relatively well by carefully minimizing time spent on my feet. In fact, I was seated off-stage in the studio, chatting with the riders while awaiting the green light, when team marketing boss Alessandro Cicognani casually asked, "Nicky, can you please put on your team hat?" When the Kentucky Kid turned to me expectantly, the immediate realization of what I was about to endure made my head swim.

To this day, the memory of that fraught excursion is a blur punctuated by moments of clarity—my bizarre gait as I hurried through the building; the door to the Ducati Corse office requiring multiple swipes of my key card; madly rummaging through a metal cabinet; again staggering through the empty hallways; and finally bursting into the studio with one red flat-brim cap triumphantly in hand, just as the spotlight followed Staffelli onto the stage. I was a bit sweaty and breathless during the subsequent interview with a behatted Nicky, but it was a rare public performance during which my predominant emotion was more relief than nervousness.

Have a Moto story you'd like help telling for free? Email chris@jonnummedia.com

The Case of the Inverted ’Taco

When a Sherpa T encounters two Norton P11s in the desert, its world quickly gets turned upside down.

Back when I was riding District 37 enduros in the 1960s and ’70s, you’d see a much wider variance in motorcycle types lining up to compete than is the case in this age of specialization. My own ride—a 1967 Norton P11—was a prime example; while a 380 pound, 745cc parallel-twin-powered bike now seems more appropriate for adventure riding than off-road racing, the model was fast and stable enough back then that San Gabriel MC's Mike Patrick rode one to the ’68 Heavyweight No. 1 plate in Southern California. Some other riders preferred lighter, more nimble machines, and encounters between the different solutions didn’t always go smoothly….

My late brother Corky had a P11 as well, and the same year that Patrick was ruling hare & hounds, we entered our Nortons in the Prospectors MC Enduro at Red Rock Canyon. As was our typical approach, I was handling timekeeping duties, with Corky following my lead, and we were having a decent day. At one point, the course took us into Freeman Gulch, where a bottleneck put us both behind schedule, and once we were through, we began hustling along the rocky-but-open side-hill trail in an effort to catch up to our minute.

Before long, we approached another rider from an earlier minute, and it was clear from a distance that he was a bit unsteady, standing on his pegs the entire time. As we closed in, I could see that he was riding a Bultaco Sherpa T trials bike, which didn’t have much of a seat. Based on the Sherpa N 250 trail bike, the trials version—campaigned in its intended application by pros like Sammy Miller and Mick Andrews—featured revised geometry, and perhaps it wasn't ideal for negotiating rock fields at a quick clip, whereas our Curnutt-suspended Nortons were relatively planted.

When encountering two Nortons in the desert, a Sherpa T quickly has its world turned upside down.

Corky and I soon closed to the ’Taco’s rear fender, and as we still hadn’t caught up to our minute, I disengaged my clutch and gave the throttle a quick twist, the twin high exhausts emitting a healthy bellow that was intended as friendly encouragement to make way. Alas, apart from a startled shudder, the Sherpa pilot didn’t react, so I decided to move closer before gunning the engine again. It so happens I didn’t get that opportunity, as a miscalculation resulted in my Norton giving a love-tap to the Bultaco’s rear tire.

Although the P11 barely felt the impact, the ’Taco immediately veered off the trail and pitched off its rider, who tumbled several feet down the slope before rolling to a stop. Concerned, Corky and I halted in the trail, and as the rider struggled to a sitting position and fumbled for his goggles, all of our eyes settled on the Sherpa T. Incredibly, the little bike had come to a trailside rest perfectly balanced upside-down on its handlebar and seat, like a bicycle having a flat tire repaired, its still-idling engine spinning the rear wheel and sending puffs of blue two-stroke smoke from the stubby exhaust. Apparently, trials bikes really do have good balance at low speeds….

The way I remember it, Sherpas had a rubber plug in place of a screw-on gas cap, but I’m unable to confirm that via Bultaco websites (please post a note in the comments section if you have info). Whether that's the case or the cap simply hadn't been fully tightened, it suddenly popped free from its home, and as we three stunned spectators looked on, the tank’s contents glugged out into the dirt and slowly trickled down the hill. Before anyone had fully processed that, the Sherpa’s engine coughed and expired, the rear wheel shuddering to a stop.

“Ahem. Ermmm… you okay?” I asked, awkwardly breaking the desert silence.

The rattled rider shifted his gaze from his inverted bike to me before giving himself a distracted onceover. “Ye-, yeah, I guess so,” he stammered.

Corky and I glanced at each other, shrugged in unison, kicked over our engines and headed down the trail, the big Nortons once again in their element.

The father of Jonnum Media founder Chris Jonnum, Jerry is a lifelong motorcycle enthusiast and former amateur off-road racer. Have a Moto Story you'd like help telling for free? Email chris@jonnummedia.com.

The Original GoPro

Long before the advent of GoPro cameras, Peter Starr was pioneering the use of helmet cameras in motorcycle racing.

Like everyone, I enjoy seeing all the ways POV video cameras like GoPros are being used with motorcycles these days, but it wasn't always so easy. Back when I was filming motorcycles in the 1970s, we had to build our own helmet cameras.

The first time we did one was an open-face helmet in 1975, when I was doing a show called “The All American Race” about dirt track racing. The helmet had a four-pound film camera on one side and a four-pound lead weight on the other for balance, which is a lot of momentum on your head when you’re going over 100 mph. There had been helmet cameras for skiers before that—I think Warren Miller had one when he was doing his ski movies—but the needs were different for motorcycle racing.

I learned from my first camera helmet that we really needed it to be comfortable and safe, so a year later we made the first full-face version, which had detachable side pods carrying the camera and weight. We measured what force it would take to shear the screws that held on the side pods, so that on impact they would detach and not be driven into the helmet injuring the rider. You’d lose the camera, but the rider would be safe and the helmet would retain its integrity. I think that was the best thing to happen to helmet photography.

Yvon Duhamel models one of Peter Starr's early film-camera helmets. (Courtesy of Peter Starr)

Barry Sheene and Steve Baker were the first ones to wear it, when we filmed the 1976 Race of the Year at Mallory Park—footage that would ultimately appear in Take it to the Limit. The original camera would only carry 50 feet or 90 seconds of film, 16mm cartridges for old gun cameras from World War II or the Korean War. That sometimes wasn’t enough, so we had to build one that would carry 100 feet of 16mm film, which would last three minutes. Over time, I built several other helmets in different sizes that we’d bring with us to the races—because you never knew who was going to ride for you—or to carry different types of cameras. When Roberto Pietri (father of Robertino) rode for us at Daytona in about 1982, he rode with both the open-face and full-face helmets. At the twisty tracks like Loudon he preferred the open-face helmet but for high-speed tracks such as Daytona, the safety of the full-face helmet was more comforting.

To be quite honest, they don’t come any better than the riders we were using. In road racing it was Sheene, Baker, Pietri, Yvon Duhamel and Kenny Roberts; in dirt track it was Corky Keener, Gary Scott, Rex Beauchamp and Mert Lawwill; and in motocross it was Roger De Coster, Marty Smith, Bob Hannah, David Bailey, Jeff Ward and Darryl Schultz. (The helmet camera was a little heavy for some of the motocross guys, so we also built a backpack with a shoulder mount so the camera looked over the shoulder.) We never had a single problem with the helmet cameras, and I think that’s mainly because of the quality of riders we were using. They were good, so we had to be too. The idea of failure was simply not in the cards.

Those guys would do everything they could to help you, which is amazing when you think about it. Back when we started making films about motorcycling in the ’70s, no one else was doing it, so maybe that’s why the riders were only too willing to help. They loved the idea that someone was making a film, and that we were the first to do “barter” syndication of motorcycle shows on television. They liked being a part of it.

Anyway, we continued using those camera helmets until video came out, at which point people said, “Oh, that weighs a lot less and is a lot less intimidating to wear and to look at.” Video cameras became the thing, and there were no more film helmet cameras.

I have no idea what it would be like to do a Take it to the Limit film today. The technology would obviously make the POV filming easier, but I wonder if it would be as easy to work with the riders.

Peter’s book on the making of Take it to the Limit, as well as DVDs of the movie itself, are available for sale at http://www.motodvd.com. Have a Moto Story you want help telling for free? Email chris@jonnummedia.com.

The Hayden Hauler

With the 2017 World SBK season just around the corner, Team Red Bull Honda's Nicky Hayden remembers traveling to the races as an amateur

Road racing season is approaching, and by the time this story gets posted I’ll be in Australia for the last pre-season test and the first round of the 2017 World SBK Championship. I’m fortunate to get to fly to the races these days, but back when I was an amateur, the transportation was just a bit more… modest.

Almost exclusively, our family got to the races in a box van we used to own, that my dad had decked out in “Earl’s Racing Team” livery. That thing was our garage when we were at the track, and since it had a couch in the back and a “deck” on top of the box to watch the races from, I guess it could technically be called our hospitality unit too. Although we’d often get a hotel room at the races, it was usually so crowded that some people would just use the room’s shower and actually sleep in the van—so it served as lodging as well!

Mainly though, it was our hauler. For many of the races, we’d have all five of us kids, both of our parents and maybe a friend and a mechanic or two, so it could get pretty crowded in there—and that was just the people! It might be one of his fish tales, but my dad swears we used to fit in 12 or 14 bikes sometimes, although many of them were just 60s or 80s. To do that, we had to build a second level in back, sort of a poor man’s version of what the modern factory haulers do; first we’d fill up the ground floor, and then we’d take some folding tables that we used at the track and rest them on a T bracket and the lower bikes to serve as the floor of the second level.

Even that wasn’t always enough though. I remember one time we were getting ready to head home from Florida, and we had somehow accumulated enough stuff—I think maybe we gained a motorcycle, some trophies and a few other things at the race—that there literally wasn't enough room for everything. We ended up having to sell a tent and some tires and leave a couple gas cans behind.

The Hayden wrecking crew poses with their trophy haul behind the family box van. (Hayden family photo)

Everybody knows the deal where you try to call shotgun when it’s time to get in the vehicle, but for us kids, the spot to fight over was sitting on the cooler between the two front bucket seats. It may not have been so comfortable, but it gave you a good view of the road and you could control the radio and the CB. The only downside was that when you stood up for something, one of your brothers would probably open the lid so that if you weren’t paying attention, you’d fall into the ice water when you sat back down!

Of course that’s assuming you weren’t actually behind the steering wheel; depending on who's asking, I may or may not have put a pillow behind my back so that I could reach the pedals before I was “of age.” That probably wouldn't fly these days.

I remember one time we were headed across Texas early in the morning, when my dad asked my older brother Tommy to drive for a while so that he could climb up into the bunk and get some sleep. Not long after he drifted off, we kids spotted a sign for a water park, so we made an executive decision to pull over and wait for it to open at 10 a.m. By the time my dad popped his head out of the bunk, he figured we would be halfway home, so it was a bit of a rude awakening when he found out we were behind schedule by quite a bit.

There are a ton of fun stories based around that old box van, and maybe sometime I’ll share a few more. Like I said, it was pretty basic, but back in those days we kids thought it as the ultimate factory hauler.

Check out Nicky's personal website, and follow him on Twitter. Have a Moto Story you'd like help telling for free? Email chris@jonnummedia.com

Corky and the Headlights

"Pointing a flashlight at the AAA map in my lap, I did some calculations and determined that about an hour and a half separated us from Flagstaff—if the headlights would hold out that long."

“The dash light just went out,” said Uncle Corky, grimly pointing at the little pickup’s now-black instrumentation. “All we have left now are the headlights.”

We were headed home to Southern California after an amazing trail-riding trip to Silverton, Colorado, my Mazda SE5 loaded down with our Honda XRs and camping equipment, and towing a tent trailer. The mini truck's heavy burden made for slow going, so the sun had long since set when we trundled past Four Corners, which was right around the time I noticed the trailer’s lights flicker off in my rear-view mirror.

Following a pause for a fruitless investigation and a change of drivers, we once again hit forlorn Route 160 west, only to be plagued, one by one, with a series of additional electrical failures, starting with the taillights and proceeding to the horn, cab lights, turn signals and now the dash. Our concern was mounting, and as midnight ticked by, it seemed that we were all alone in the dark Arizona desert.

Our plan had been to stop at a rest area to spend the night, but with the Mazda’s headlights still gamely brightening a sliver of the Navajo Indian Reservation, Corky wisely pointed out that the situation dictated a change of plans.

“The starter’s probably out of commission too,” he said. “If we turn off the motor, we might be stranded.””

Pointing a flashlight at the AAA map in my lap, I did some calculations and determined that about an hour and a half separated us from Flagstaff—if the headlights would hold out that long.

Ever since I was in grade school, my dad’s older brother had taken it upon himself to ensure that I had a full appreciation of the American Southwest, his irregular work schedule and lifelong bachelorhood enabling us to make the best of my vacations. From fishing at Convict Lake in the Sierras to dirt biking at Dove Springs in the Mojave Desert, my youth had been seasoned with adventures with Corky, and this was one of the best—or at least it had been until the return trip.

It was 2:30 a.m. when we finally approached Flagstaff, breathing a sigh of relief as Corky downshifted so that he could seek out a suitable stopping point. He found what he was looking for in a wide, graded dirt road that descended from the left side of the highway, and we parked to one side and drifted off for a few hours’ uncomfortable slumber in the Mazda’s cramped cab.

Uncle Corky aboard his BSA in Silverton during an earlier trip to Colorado. (Gail Shannon photo)

After being jolted awake at sunrise by a convoy of trucks lumbering by (it turns out our impromptu lodging area was also a logging area by day), we rubbed the sleep out of our eyes, bump-started the Mazda on the dirt downhill, found a turnout to reverse direction and—being careful not to stall—headed into town. In the daylight and civilization, our predicament didn't seem nearly as dire, and some crawling around in a Pep Boys parking lot resulted in a successful diagnosis: the trailer connector harness had been damaged (we both now recalled I’d run over a retread just before Four Corners), and the exposed wires had occasionally contacted the trailer’s metal tongue, popping electrical fuses one at a time. Thanks to the headlights using a separate circuit, they had been spared the fate of the other electrical functions, and after we taped up the harness and replaced the blown fuses, the remainder of our drive home was relatively uneventful.

Although I didn't realize it at the time, my impending move away to college—and then a career, then marriage and a kid—would significantly curtail my camping and riding trips with Corky, but he was frequently in my thoughts last year as he struggled with poor health. Last month, Uncle Corky’s name was added to the long list of those who succumbed to 2016’s ruthless toll, and while he wasn’t as high-profile as many, I’m feeling his loss acutely as I peer down the unknown road of a New Year.

Have a Moto Story you'd like help telling for free? Email chris@jonnummedia.com